Chapter 1 Calculus is a Rock

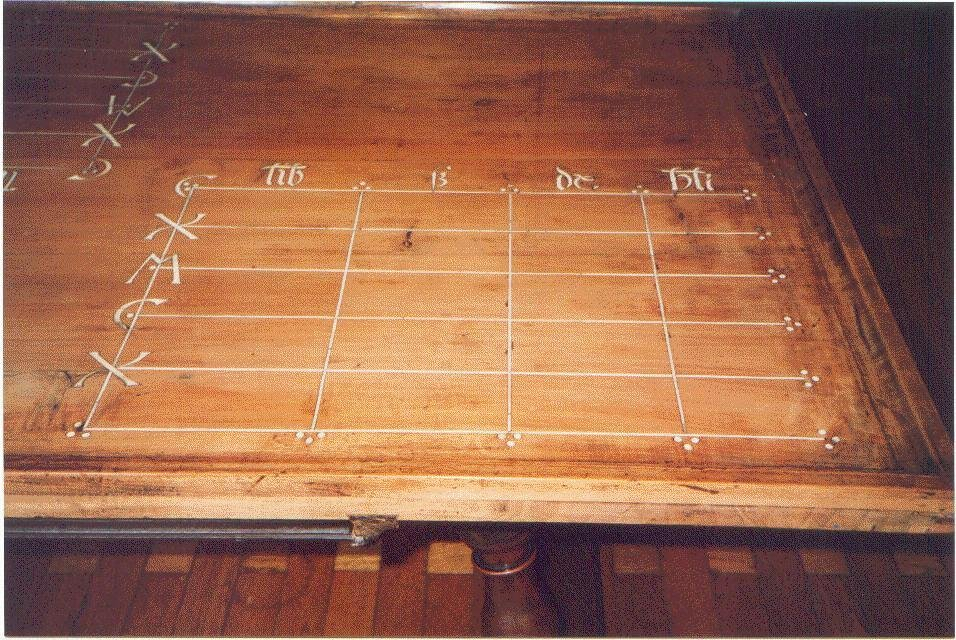

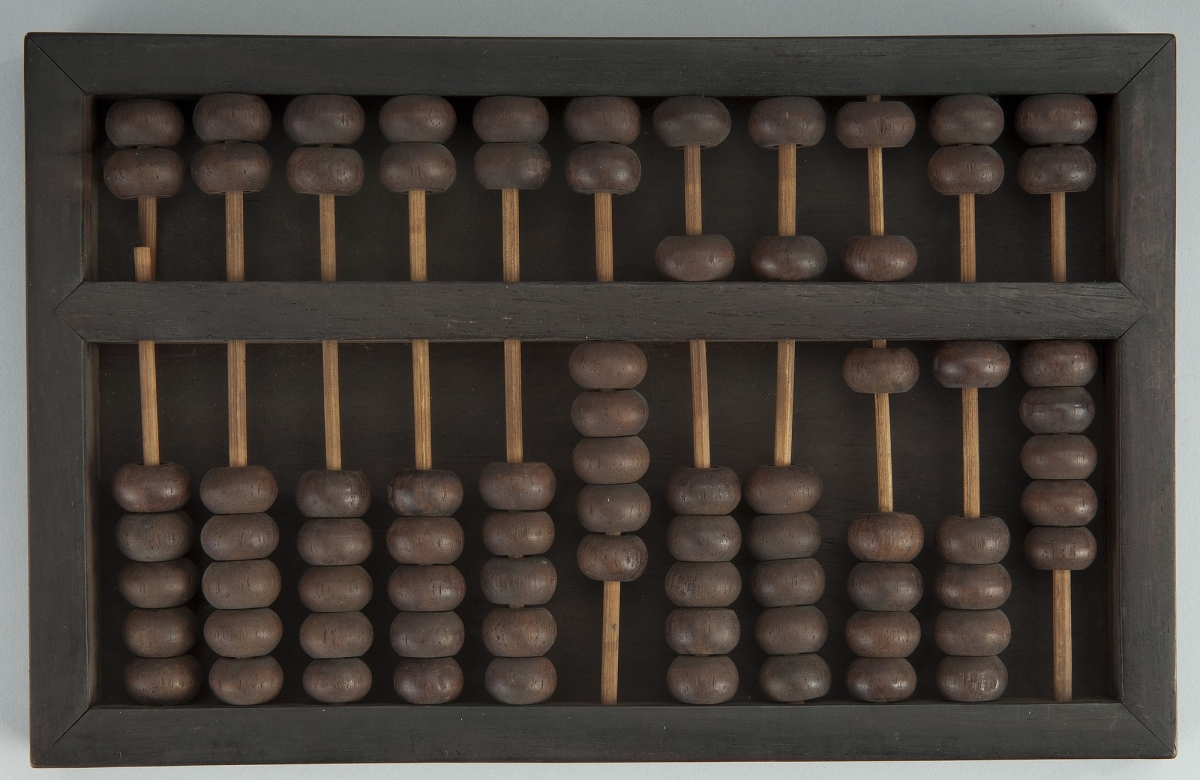

Commercial transactions were hard to do using Roman numerals. So in Europe during the Middle Ages such computations were usually done using pebbles on a small table called a counting board. The board was marked off so that placing a pebble here meant “one,” there meant “ten,” over there meant “a hundred,” and so on. Think of an abacus. Obviously the only computational skills a merchant needed were a thorough knowledge of rules for moving the pebbles and how to read the board afterward.

The Latin word for “rock” or “pebble” is “calculus.” Thus the English word “calculus” has come to refer to any computational scheme where it was not really necessary to understand the computations in order to apply them, at least for basic applications.

There are many calculuses (calculi?) in mathematics but the one we will be studying is of such profound and fundamental importance that it has come to be called The Calculus or just Calculus.

Nevertheless it is a calculus in the original sense. That is, it is possible to simply memorize the rules for manipulating symbols (“move the pebbles”) and thereby solve a great many otherwise very difficult problems without any very deep understanding. There is nothing wrong with using Calculus this way. Indeed, this is precisely what it was invented to do. The difficulty is that those who learn only to manipulate symbols are in a position similar to the merchants of the Middle Ages. They can do the calculations but they only understand how to move the pebbles (use the notation). If a problem comes up that is outside the reach of their pebbles they are completely helpless.

This was not a problem for say, Marco Polo. He rarely had to do much mathematics besides add, subtract, multiply and divide. A deep understanding of these operations is not needed for the simple financial transactions of the Middle Ages. However, in the modern era such routine, rudimentary computations are done by machines. The role of humans is to figure out how to apply the fundamental concepts in novel arenas and in novel ways. Simply learning to compute, without a deeper understanding of the principles involved, is not a foundation upon which a modern education can be built. Modern practitioners must be flexible, and flexibility comes from a deep understanding of principles.

As you will soon see many otherwise very difficult problems become straightforward, even simple if we know how to manipulate Calculus notation (move the pebbles) correctly. So simple in fact, that it is easy to confuse the manipulation of notation with understanding. Don’t make that mistake.

Notation is not mathematics. Notation is simply the best way we’ve found for representing mathematical ideas and communicating them to other people. Notice that we did not say that it is the best way. Only that it is the best we’ve found so far. Sometimes our notation falls short of our needs; sometimes far short. When it does only a deep understanding of fundamental concepts will clarify the problem for you.

Even though the rules for manipulating the notation of Calculus were designed to be used blindly, this does not make them unimportant. If anything it is more important in the modern era than it has ever been that students learn to read the notation with understanding and to use the computational rules skillfully because it is through mastering these fundamentals that the underlying concepts emerge and become clear.

So we will begin with the Calculus notation, and the rules for its manipulation. But we (your teacher, and the authors of this book) cannot master this for you. We are only your guides. You must stay focused on understanding, not mere computation. The process is slow. It takes time and practice and it can be very frustrating. Prepare yourself. Arrange your study schedule to give yourself as much time for practice as you can possibly manage. Do not accept simply “getting the right answer” as “good enough.” If you can correctly perform some computation but don’t take the time to understand why that particular manipulation of the symbols led you to the “right answer” then you are wasting your time. Your goal is to understand, not to compute.

It may surprise you to learn that when it was first invented the validity of the Calculus was very suspect. The underlying ideas were very ad hoc and did not stand up to close scrutiny at all. Indeed, the foundations of the topic were so murky that the only reason Calculus remained viable was the simple fact that it worked. Or at least, it seemed to. This was taken as evidence that the underlying principles were valid but no one was very comfortable with the fact that those principles could not be unambiguously stated. It took about \(200\) years to finally work out a supporting logical foundation that explained why the symbol manipulations of Calculus worked and, perhaps more importantly, when they wouldn’t work.

This text follows the history of our topic. In the first part (“From Practice . . .”) we begin with the rules for performing Calculus computations — we’ll learn to move the pebbles. When these have been mastered we’ll learn to use these computational methods to solve some (hopefully) interesting and (definitely) substantial problems.

We will not address the logical underpinnings of the Calculus until the second part (“. . . To Theory”) where we will examine the logical support structure that took some the greatest minds our species has known almost \(200\) years to develop. Naturally this will require a shift in our focus. In the first part of this text you will learn how to use Calculus. In the second part you will learn why it works the way that it does.

This will be hard. At times it will be very hard. But it is worth the effort. At the other end, when it all comes together, there is a transcendent beauty to the Calculus which is impossible to convey to the uninitiated. A poet once wrote, “Euclid alone has looked on beauty bare,” but this is not true. Everyone who has studied and understood mathematics beyond the level of moving the pebbles has seen the same beauty that Euclid saw. If you have never seen it this is your chance.