Section 3.2 Some Preliminaries

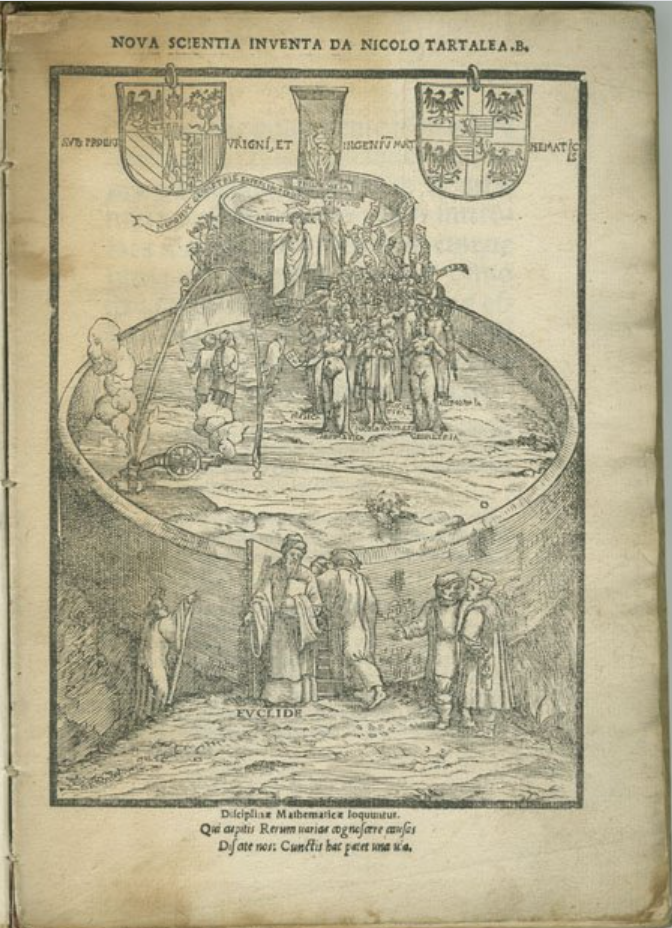

In \(1537\) Niccolo Fontana (1500–1557), also known as “Targtaglia” (The Stutterer), wrote a book titled Nova Scientia (New Science) wherein he analyzed the motion of objects moving under the influence of gravity near the surface of the earth as it was understood at the time.

There is much allegory in the title page of his book. Inside the large ring is a group of Muses surrounding Tartaglia and observing the trajectory of a cannonball. This represents the fact that this was one of the first works which studied the science of projectile motion using mathematical principles rather than empirical data and guesswork. At the door of the larger ring is Euclid, representing the notion that one can only enter through an understanding of Euclid’s Elements (Geometry). Clearly the man trying to scale the wall does not understand Geometry. His ladder is far too short.

The smaller, slightly raised ring is occupied by Philosophia (wisdom) seated on a throne. Of course, the only entrance to the ring of philosophy, and therefore understanding, is through the larger ring of mathematics. At that gate are Aristotle (384–322 BC) (on the mathematics side) and Plato (427–347 BC) (on the philosophy side). On the banner is the motto of Plato’s Academy, “Let no one ignorant of geometry enter.” Of course, such allegory is open to interpretation, but it seems pretty clear that Geometry (mathematics) would play an important role in the New Science.

Aside: Historical Context.

The caption below the illustration means, “The Mathematical sciences speak: Who wishes to know the various causes of things, learn about us. The way is open to all.”

From the beginning of the Renaissance to the present day the use of mathematics to describe and analyze physical phenomena has become ever the more normal mode of analysis in science. At first the Geometry of the Greeks, including Trigonometry, was at the forefront, but as time went on newer methods were invented. Primary among these were Algebra and then, eventually, Calculus.

Algebra came first but it merged with Geometry to form what we now call Analytic Geometry. When Calculus was invented it supplemented, enhanced, and expanded its predecessors.

None of the other fields of mathematics disappeared. Geometry, Trigonometry, Algebra, and Analytic Geometry remain very useful tools in science. But they have, in a sense, become subordinate to Calculus.

There are physical problems that are very difficult to solve using either Algebra or Geometry but which become relatively easy once Calculus has been mastered. Attempts to address those difficult–to–solve problems are what led to the invention of Calculus and several of the very ingenious techniques developed were very Calculus–like. In this chapter we will look briefly at some of these pre–Calculus techniques.

Warning: You may be tempted to disregard this chapter and get on to “the Calculus part.” This is an error. The story of Calculus, what sorts of problems it was invented to address, and why the tools of Calculus developed in the way that they did, will help you understand what Calculus is, and what it is not.