Example 2.3.1.

The lengths of two sides of a triangle are \(a\) and \(b\text{.}\) If the third side is chosen in such a way that the area of the triangle is as large as possible what is the length of the third side?

You may be able to intuit the correct answer to this problem. That’s OK, but you should try to solve it, too. By “solve” we mean that you should be able to explain to someone with the same mathematical skills you have at the moment why your answer is correct.

Aside: Comment.

Before reading further do your best to solve this problem. We’ll wait.

At first it is difficult to see where to begin. (That’s why it’s called a problem.) Don’t let this stop you! In our experience the most common mistake is giving up too soon.

Don’t. Do. That. Keep thinking.

Solution. (Partial)

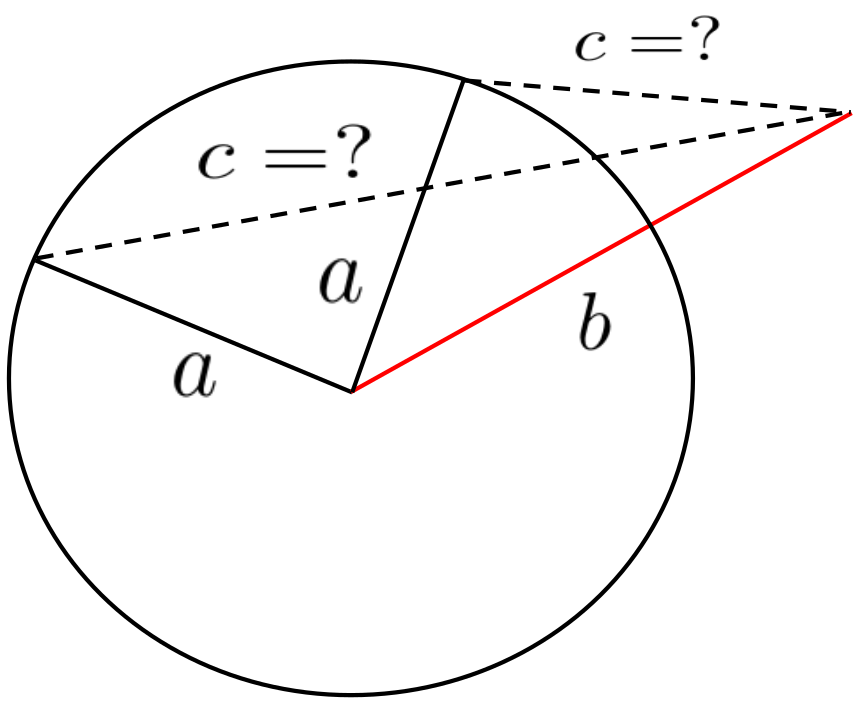

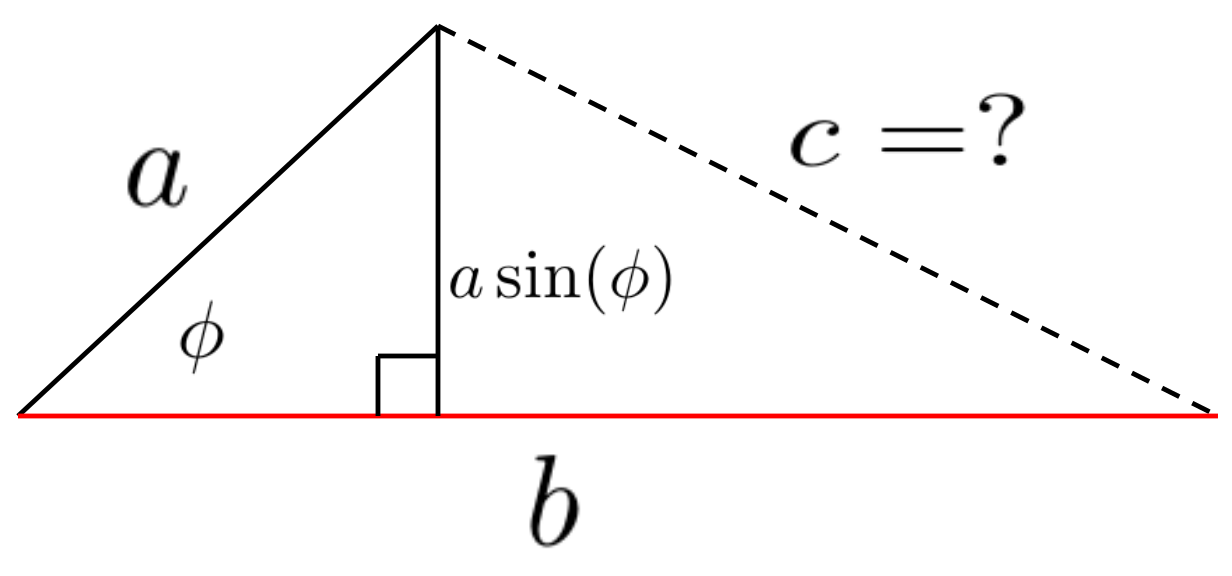

Since we know the lengths of the sides \(a\) and \(b\) of our triangle let’s draw it. The sketch below would be typical. The question is, what length for side \(c\) makes the total area enclosed by the triangle as large as it can possibly be?

Now what?

Well, this looks like a right triangle doesn’t it? If it is a right triangle, then we can find the length of \(c\) via the Pythagorean Theorem: \(c=\sqrt{a^2+b^2},\) right?

Before you go on take a moment and really think about this problem. Can it really be that simple? Can you find any flaws in our reasoning.

Once you think about it you see that we have no reason to believe that the triangle we seek must be a right triangle. It was completely accidental that we drew our diagram that way. If this seems like a simple-minded mistake, the sort of mistake that you would never make, be careful. It is a mistake to rely too heavily on the diagrams we draw. But it is an easy mistake to make, especially when the problems are more complicated, because as problems get complex we will need to rely on visualization more and more. This was not a dumb mistake. It was just a bit careless, and it is easy to be careless, especially when we first start thinking about a problem.