Section 17.4 Limit Laws (Theorems)

If we can prove each of the limit laws in Chapter 14 rigorously (i.e, using Definition 17.3.1) we will have provided a rigorous foundation for Differential Calculus. We will address these now.

Subsection 17.4.1 The Limit of a Sum

To prove the limit laws we will need to make extensive use of what is called the Triangle Inequality. We state and prove the Triangle Inequality here so that we can cite it as needed.

The proof of the Triangle Inequality relies on equation (17.5) from Digression: Absolute Value, again.

Proof of the Triangle Inequality.

Clearly \(-\abs{x}\leq x \leq \abs{x}\) and \(-\abs{y}\leq y \leq

\abs{y}.\) Adding these together we have

\begin{align*}

-\abs{x}-\abs{y}\amp\leq x+y\leq \abs{x}+\abs{y}\\

\underbrace{-\left(\abs{x}+\abs{y}\right)}_{-B}\amp\leq \underbrace{x+y}_A \leq \underbrace{\abs{x}+\abs{y}}_{B}.

\end{align*}

so by (17.5) we have \(\abs{x+y} \leq \abs{x}+\abs{y}\text{.}\)

The Limit Laws we need to prove are:

- Theorem 14.1.7:

- The Limit of a Constant is the Constant.

- Theorem 14.1.1:

- The Limit of a Sum is the Sum of the Limits

- Theorem 14.1.2:

- The Limit of a Product is the Product of the Limits

- Theorem 14.1.16:

- The Limit of a Composition is the Composition of the Limits, and

- Theorem 14.1.19:

- The Squeeze Theorem

We will provide a proof of the “limit at infinity” version of each of these Theorems using Definition 17.2.13. We will leave the proof of the “limit at a real number” version using the Definition 17.3.1 as an exercise for you. In every case you can model your scrapwork and proof on the ones we provide.

Theorem 17.4.2. The Limit at Infinity of a Constant Function is the Constant.

Suppose \(L\) and \(K\) are real numbers. If \(f(x)=K\) for all \(x\gt L\) then \(\limit{x}{\infty}{f(x)}=K\text{.}\)

Proof.

Let \(\eps\gt 0\) be given. Take \(B=L.\) Then if \(x\gt B\) we see that

\begin{equation*}

\abs{f(x)-K}=\abs{K-K}=0\lt \eps.

\end{equation*}

Therefore

\begin{equation*}

\limit{x}{\infty}{f(x)}=K.

\end{equation*}

The formalism we’re using requires that we specify some value for \(B\text{.}\) It was convenient to specify \(B=L\text{,}\) but in this proof any value for \(B\ge L\) would have worked as well.

Theorem 17.4.3. The Limit at Negative Infinity of a Constant Function is the Constant.

Suppose \(U\) and \(K\) are real numbers. If \(f(x)=K\) for all \(x\lt U\) then \(\limit{x}{-\infty}{f(x)}=K.\)

Problem 17.4.4.

Theorem 17.4.5. The Limit at a Point of a Constant Function is the Constant.

Suppose \(K\) is a real number. If \(f(x)=K\) near \(a\) then

\begin{equation*}

\limit{x}{a}{f(x)}=K\text{.}

\end{equation*}

Problem 17.4.6.

Hint.

Despite the apparent simplicity of this problem there is a lot going on here. Recall that “near” means that \(f(x)=K\) on some open interval, say \((c,d)\text{,}\) containing \(a\) except possibly at \(a\) (see Definition 14.1.6). You need to find a \(\delta\gt0\) such that if \(-\delta\lt x-a \lt\delta\) then \(f(x)=K\text{.}\) That is, you need an interval of length \(2\delta\) with \(a\) as the midpoint where \(f(x)=K\text{.}\) But there is no guarantee that \(a\) is the midpoint of the interval \((c,d)\text{.}\) This would be an excellent time to engage your visual intuition by drawing a sketch so you can “see” the problem.

Theorem 17.4.7. The Limit of a Sum at Infinity.

If \(\limit{x}{\infty}{f(x)}=L_f\) and \(\limit{x}{\infty}{g(x)}=L_g\) then \(\limit{x}{\infty}{\left(f(x)+g(x)\right)}=L_f+L_g.\)

Scrapwork 17.9.

As always we begin by assuming that \(\eps\gt 0\) has been given.

We want to show that if \(x\) is large enough (larger than some specified \(B\)) then

\begin{equation}

\abs{(\textcolor{red}{f(x)}

+\textcolor{blue}{g(x)})-(\textcolor{red}{L_f}+\textcolor{blue}{L_g})}\lt \eps.\tag{17.8}

\end{equation}

The only information we have to work with is the knowledge that

\begin{equation*}

\limit{x}{\infty}{f(x)}=L_f\text{ and

}\limit{x}{\infty}{g(x)}=L_g,

\end{equation*}

which means that we can make \(\abs{f(x)-L_f}\) and \(\abs{g(x)-L_g}\) as close to zero as we wish, provided we make \(x\) large enough. Rewriting the left–hand side of equation (17.8) and invoking the Triangle Inequality we see that

\begin{align*}

\abs{(\textcolor{red}{f(x)}

+\textcolor{blue}{g(x)})-(\textcolor{red}{L_f}+\textcolor{blue}{L_g})}

\amp =

\abs{(\textcolor{red}{f(x)}-\textcolor{red}{L_f})+(

\textcolor{blue}{g(x)}-\textcolor{blue}{L_g})}\\

\amp \le \abs{\textcolor{red}{f(x)}-\textcolor{red}{L_f}}+\abs{

\textcolor{blue}{g(x)}-\textcolor{blue}{L_g}}.

\end{align*}

But as we’ve observed we can make \(\abs{f(x)-L_f}\) and \(\abs{g(x)-L_g}\) as close to zero as we wish, provided we take \(x\) large enough. To be precise, there is a number \(B_f\) such that if \(x\gt B_f\) then \(\abs{f(x)-L_f}\lt\frac{\eps}{2}\text{.}\) Similarly there is a number \(B_g\) such that if \(x\gt B_g\) then \(\abs{g(x)-L_f}\lt\frac{\eps}{2}\text{.}\)

Since we need for both of these things to happen a sufficiently large value of \(x\) is one where \(x\gt B_f\) and \(x\gt B_g\text{.}\)

END OF SCRAPWORK

Proof.

Let \(\eps\gt 0\) be given. Since \(\limit{x}{\infty}{f(x)}=L_f\) there is a bound, \(B_f\) such that if \(x\gt B_f\) then \(\abs{f(x)-L_f}\lt \frac{\eps}{2}.\) Since \(\limit{x}{\infty}{g(x)}=L_g\) there is a bound, \(B_g\) such that if \(x\gt B_g\) then \(\abs{g(x)-L_g}\lt \frac{\eps}{2}.\) Take \(B= \max(B_f,B_g)\text{.}\) Then if \(x\gt B\) then \(x\gt B_f\) and \(x\gt B_g\text{.}\) Thus by the Triangle Inequality (Theorem 17.4.1)

\begin{align*}

\abs{(f(x)+g(x))-(L_f+L_g)}\amp = \abs{(f(x)-L_f)+(g(x)-L_g)}\\

\amp \le {\abs{f(x)-L_f}}+{\abs{g(x)-L_g}}\\

\amp \lt \frac{\eps}{2} + \frac{\eps}{2}\\

\amp= \eps.

\end{align*}

Therefore \(\limit{x}{\infty}{\left(f(x)+g(x)\right)}=L_f+L_g.\)

Problem 17.4.8.

Theorem 17.4.9. The Limit of a Sum at Negative Infinity.

If \(\limit{x}{-\infty}{f(x)}=L_f\) and \(\limit{x}{-\infty}{g(x)}=L_g\) then \(\limit{x}{-\infty}{\left(f(x)+g(x)\right)}=L_f+L_g.\)

Problem 17.4.10.

Theorem 17.4.11. Limit of a Sum at a Point.

Suppose that \(a\) is some real number, \(\limit{x}{a}{f(x)}=L_f\) and \(\limit{x}{a}{g(x)}=L_g\text{.}\) Then

\begin{equation*}

\limit{x}{a}{\left(f(x)+g(x)\right)}=L_f+L_g.

\end{equation*}

Subsection 17.4.2 The Squeeze Theorem

Theorem 17.4.12. The Squeeze Theorem at Infinity.

If \(\alpha(x)\le f(x)\le \beta(x)\) on some interval, \((c, \infty)\) and

\begin{equation*}

\limit{x}{\infty}{\alpha(x)} =

\limit{x}{\infty}{\beta(x)} = L

\end{equation*}

then \(\limit{x}{\infty}{f(x)} = L\) also.

Proof.

Let \(\eps\gt0\) be given. Since \(\limit{x}{\infty}{\alpha(x)} = L\) there is some a real number \(B_\alpha\text{,}\) such that if \(x\gt B_\alpha\) then \(\abs{\alpha(x)-L}\lt \eps\text{.}\) From (17.5) we see that for \(x\gt B_\alpha\text{:}\)

\begin{equation*}

-\eps \lt \alpha(x)-L \lt \eps.

\end{equation*}

Similarly there is a real number \(B_\beta\text{,}\) such that if \(x\gt B_\beta\) then \(\abs{\beta(x)-L}\lt \eps\text{.}\) So for \(x\gt B_\beta\text{:}\)

\begin{equation*}

-\eps \lt \beta(x)-L \lt \eps.

\end{equation*}

Take \(B=\max(c,

B_\alpha, B_\beta)\text{.}\) Then if \(x\gt B\)

\begin{equation*}

-\eps \lt \alpha(x)-L \lt f(x)-L \lt \beta(x)-L \lt \eps.

\end{equation*}

In particular, \(-\eps \lt f(x)-L \lt \eps \) so from (17.5) we see that \(\abs{f(x)-L}\lt \eps \text{.}\) Therefore \(\limit{x}{\infty}{f(x)} = L\text{.}\)

Problem 17.4.13.

Theorem 17.4.14. The Squeeze Theorem at Negative Infinity.

If

\begin{equation*}

\alpha(x)\le f(x)\le \beta(x)

\end{equation*}

on some interval, \((-\infty,c)\) and

\begin{equation*}

\limit{x}{-\infty}{\alpha(x)} =

\limit{x}{-\infty}{\beta(x)} = L

\end{equation*}

then

\begin{equation*}

\limit{x}{-\infty}{f(x)} = L

\end{equation*}

also.

Problem 17.4.15.

Theorem 17.4.16. The Squeeze Theorem, at a Point.

If \(\alpha(x)\le f(x)\le \beta(x)\) near \(a\) and \(\limit{x}{a}{\alpha(x)} = \limit{x}{a}{\beta(x)} = L\) then \(\limit{x}{a}{f(x)} = L\) also.

Subsection 17.4.3 The Limit of a Composition

Recall that at the end of Example 12.4.31 in Section 12.4 we commented that it is only true that \(\tlimit{x}{a}{f(g(x))}\) is equal to \(f\left(\tlimit{x}{a}{g(x)}\right)\) when \(f\) is continuous at \(g(a)\text{.}\)

Example 17.4.17.

Let

\begin{equation*}

f(x)=

\begin{cases}

5\amp \text{ if } x\ge1 \\

0\amp \text{ if } x\lt1

\end{cases}

\end{equation*}

and \(g(x)=\frac{x}{x+1}\text{.}\) Observe that \(g(x)\lt

1\) when \(x>0\text{,}\) that \(\tlimit{x}{\infty}{g(x)}=1\text{,}\) and that \(f\) is not continuous at \(x=1\text{.}\) We have \(f\underbrace{\left(\tlimit{x}{\infty}{g(x)}\right)}_{=1} = f(1) =5\) and \(\tlimit{x}{\infty}{f(g(x))} =

\tlimit{x}{\infty}{f\underbrace{\left(\frac{x}{x+1}\right)}_{\lt1}} =

0\text{.}\) Therefore

\begin{equation*}

f\left(\tlimit{x}{\infty}{g(x)}\right)

\neq\tlimit{x}{\infty}{f(g(x))}.

\end{equation*}

Theorem 17.4.18. The Limit of a Composition at Infinity.

Suppose \(\tlimit{x}{\infty}{g(x)}=L_g\) and \(f(y)\) is continuous at \(y=L_g\text{.}\) Then

\begin{equation*}

\limit{x}{\infty}{f(g(x))} = f(L_g) =

f\left(\tlimit{x}{\infty}{g(x)}\right).

\end{equation*}

Scrapwork 17.10.

It will be helpful to have a visual guide for this proof so we will rely on diagrams here in the scrapwork. Our finalized proof below will not.

Let \(\eps\gt0\) be given. We need to show that we can find a \(B\gt0\) such that if \(x\gt B\) then \(\abs{f(g(x))-f(L_g)}\lt\eps\text{.}\)

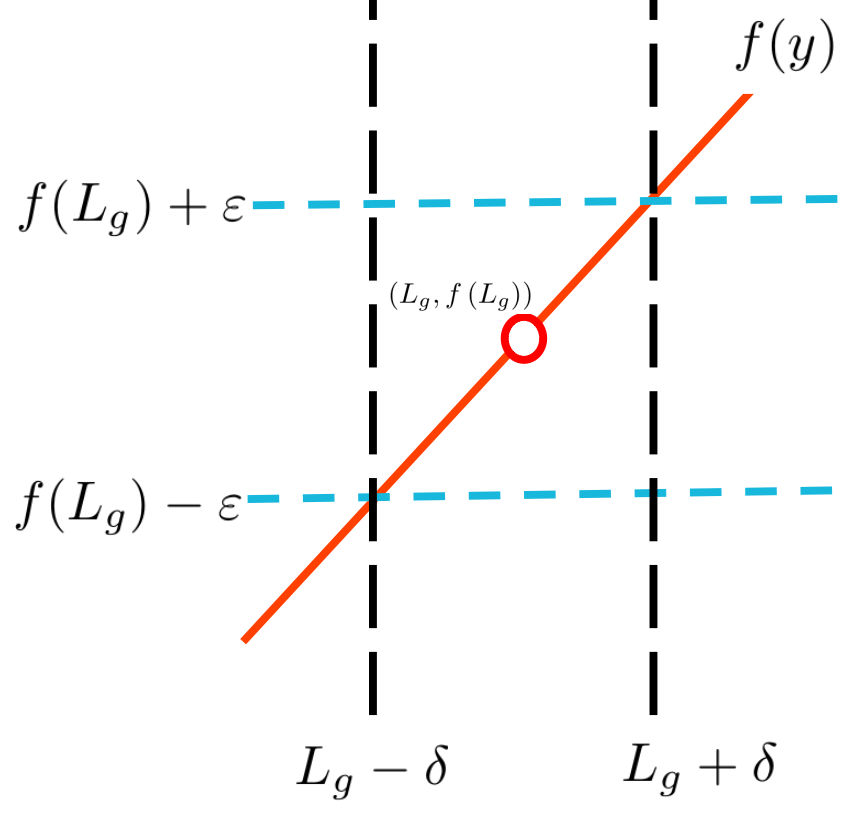

Since \(f\) is continuous at \(y=L_g\) Definition 14.1.15 tells us that \(\tlimit{y}{L_g}{f(y)}=f(L_g)\)

Thus Definition 17.3.1 tells us that there there is a real number \(\delta>0\) such that if \(\abs{y-L_g}\lt\delta\) then \(\abs{f(y)-f(L_g)}\lt\eps\text{,}\) as visualized in the sketch above.

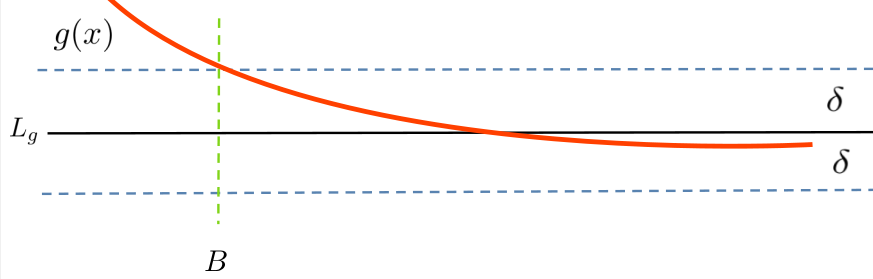

Next, consider what it means to say that \(\tlimit{x}{\infty}{g(x)}=L_g\text{.}\) It means that if we take \(x\) large enough we can make \(g(x)\) as close to \(L_g\) as we would like. In particular, we would like for \(\abs{g(x)-L_g}\lt\delta\) as in the sketch below.

Therefore, we can find a number \(B\) such that for every \(x\gt B\text{,}\) \(\abs{g(x)-L_g}\lt\delta\text{.}\) If we take \(y=g(x)\text{,}\) then we have \(\abs{y-L_g}\lt\delta\text{.}\)

From the continuity of \(f\) at \(L_g\) we know that \(\abs{g(x)-L_g}=\abs{y-L_g}\lt\delta\) means that

\begin{equation*}

\abs{f(g(x))-f(L_g)}=\abs{f(y)-f(L_g)}\lt\eps.

\end{equation*}

END OF SCRAPWORK

Proof.

Let \(\eps\gt 0\) be given. Since \(f(y)\) is continuous at \(L_g\) there is a real number \(\delta\gt0\) such that

\begin{equation*}

\text{if }\abs{y-L_g}\lt\delta\text{ then }\abs{f(y)-f(L_g)}\lt\eps.

\end{equation*}

Since \(\tlimit{x}{\infty}{g(x)}=L_g\) there is a real number \(B\) such that

\begin{equation*}

\text{ if } x\gt B \text{ then } \abs{g(x)-L_g} \lt \delta.

\end{equation*}

Take \(B\) be the lower bound needed to guarantee that \(\abs{g(x)-L_g}\lt\delta\text{.}\) If \(x\gt B\) then since \(y=g(x)\)

\begin{equation*}

\abs{y-L_g}=\abs{g(x)-L_g}\lt\delta,

\end{equation*}

and since \(\abs{y-L_g}\lt\delta\) we see, from the continuity of \(f\) at \(L_g\) that \(\abs{f(y)-f(L_g)}\lt\eps\text{.}\) Therefore \(\limit{x}{\infty}{f(g(x))} = f(L_g) =

f\left(\tlimit{x}{\infty}{g(x)}\right).\)

Problem 17.4.19.

Theorem 17.4.20. The Limit of a Composition at Negative Infinity.

Suppose \(\tlimit{x}{-\infty}{g(x)}=L_g\) and \(f(y)\) is continuous at \(y=L_g\text{.}\) Then

\begin{equation*}

\limit{x}{-\infty}{f(g(x))} = f(L_g) =

f\left(\tlimit{x}{-\infty}{g(x)}\right).

\end{equation*}

Problem 17.4.21.

Theorem 17.4.22. The Limit of a Composition at a Point.

Suppose \(\limit{x}{a}{g(x)}=L_g\text{,}\) and that \(f(y)\) is continuous at \(y=L_g\text{.}\) Then

\begin{equation*}

\limit{x}{a} {f(g(x))}=f(L_g)=f\left(\limit{x}{a}{g(x)}\right).

\end{equation*}

Subsection 17.4.4 The Limit of a Product

Theorem 17.4.23. The Limit of a Product at Infinity.

If

\begin{align*}

\limit{x}{\infty}{f(x)}=L_f \amp{}\amp{} \text{ and }

\amp{}\amp{}\limit{x}{\infty}{g(x)}=L_g

\end{align*}

then \(\limit{x}{\infty}{\left(f(x)\cdot g(x)\right)}=L_f\cdot L_g.\)

The proof of Theorem 17.4.23 is very straightforward once the following two lemmas have been proved. We state these lemmas here so that we can refer to them in the proof of Theorem 17.4.23 but the proof of Theorem 17.4.23 is not complete until these lemmas have been proved.

Lemma 17.4.24.

If \(\limit{x}{\infty}{f(x)}=L_f\) and \(\limit{x}{\infty}{g(x)}=L_g\) then \(\tlimit{x}{\infty}{\left(f(x)\cdot g(x)-f(x)\cdot L_g\right)}=0.\)

Lemma 17.4.25.

If \(\limit{x}{\infty}{f(x)}=L_f\) and \(\limit{x}{\infty}{g(x)}=L_g\) then \(\tlimit{x}{\infty}{\left(f(x)\cdot L_g-L_f\cdot L_g\right)}=0\)

Proof of Theorem 17.4.23.

Let \(\eps \gt 0\) be given. Observe that

\begin{equation*}

\abs{f(x)\cdot g(x) - L_g\cdot L_f} = \abs{f(x)\cdot g(x)

\underbrace{-f(x)\cdot L_g+f(x)\cdot L_g}_{=0} - L_f\cdot L_g}.

\end{equation*}

Adding and subtracting the same term like this is a highly non-intuitive, but common “trick.” Most mathematicians call it “adding zero” since middle terms add to zero. We (the authors) call this “uncanceling” because the middle terms cancel. It is hard to tell a priori when this trick will work. Sometimes you just have to try something and see what happens.

In this case our uncanceling allows us to use the Triangle Inequality effectively. From the Triangle Inequality we see that

\begin{align*}

\abs{f(x)\cdot g(x) - L_g\cdot L_f} \amp= \abs{f(x)\cdot g(x)-f(x)\cdot L_g+f(x)\cdot L_g - L_f\cdot L_g}\\

\amp\leq \abs{f(x)\cdot g(x) -f(x)\cdot L_g} + \abs{f(x)\cdot \textcolor{red}{L_g}

- L_f\cdot \textcolor{red}{L_g}}

\end{align*}

\begin{equation*}

\abs{f(x)\cdot g(x)-f(x)\cdot L_g}\lt\frac{\eps}{2}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\abs{f(x)\cdot L_g-L_f\cdot L_g}\lt\frac{\eps}{2}.

\end{equation*}

Take \(B=\max\left(B_1, B_2\right)\text{.}\) If \(x\gt B\) then

\begin{equation*}

\label{eq:ProdLimReturnPoint}

\abs{f(x)\cdot g(x) - L_g\cdot L_f} \leq

\underbrace{\abs{f(x)\cdot g(x) -f(x)\cdot L_g}}_{\lt\frac{\eps}{2}} + \underbrace{\abs{f(x)\cdot L_g

- L_f\cdot L_g}}_{\lt\frac{\eps}{2}}\lt \eps\text{.}

\end{equation*}

Therefore \(\limit{x}{\infty}{f(x)\cdot

g(x)}=\limit{x}{\infty}{f(x)}\cdot\limit{x}{\infty}{g(x)}\text{.}\)

Proving Lemma 17.4.24 To prove Lemma 17.4.24 we need to guarantee that if \(x\) is large enough then

\begin{equation*}

\abs{f(x)\cdot g(x)-f(x)\cdot L_g} =\abs{f(x)}\abs{g(x)-L_g} \lt \eps,

\end{equation*}

where \(\eps\) is an arbitrary, positive, real number. An “obvious” strategy is to observe that since we know that \(\tlimit{x}{\infty}{g(x)}=L_g\) it must be that if \(x\) is large enough then \(\abs{g(x)-L_g} \lt \frac{\eps}{\abs{f(x)}}\text{.}\)

But that strategy will fail. Here’s why. Definition 17.2.13 says that if \(\limit{x}{\infty}{g(x)}=L_g\) then for any single real number \(\eps\) we can find a \(B\) such that if \(x\gt B\) then \(\abs{g(x)-L_g}\lt\eps.\) But \(\frac{\eps}{\abs{f(x)}}\) is not a single real number. For each distinct value of \(x>B\) we’ll have a (possibly) different value of \(f(x)\text{.}\) We have no definition, and no theorem that says we can do this. So we can’t. That strategy won’t work. At least it won’t work in its most obvious form.

But it will work if we can replace \(\abs{f(x)}\) by some fixed value. The following lemma states that since \(f(x)\) has a finite limit, it must be bounded. This will allow us to replace \(\abs{f(x)}\) with that bound, which is a fixed parameter, in our proof of Lemma 17.4.24.

Lemma 17.4.26.

If \(\tlimit{x}{\infty}{f(x)} = L_f\) then there are positive real numbers \(N\) and \(\beta\text{,}\) such that if \(x\gt \beta\text{,}\) then \(\abs{f(x)} \lt N\text{.}\)

Proof.

Since \(\tlimit{x}{\infty}{f(x) = L_f}\) there is a positive number \(\beta\) such that if \(x\gt \beta\) then \(\abs{f(x)-L_f}\lt 1\text{.}\) So for \(x\gt\beta\text{,}\)

\begin{align*}

-1\amp\lt f(x)-L_f\lt 1\\

L_f-1\amp\lt f(x)\lt L_f+1.

\end{align*}

Now choose any positive number \(N\) with

\begin{equation*}

-N\lt L_f-1\lt f(x)\lt L_f+1\lt N,

\end{equation*}

and it follows that if \(x\gt\beta\) then \(\abs{f(x)}\lt N\text{.}\)

Problem 17.4.27.

Draw a convincing diagram of Lemma 17.4.26 and its proof.

Proof of Lemma 17.4.24.

From Lemma 17.4.26 we see that there are positive real numbers \(N\) and \(\beta\text{,}\) such that for all \(x\gt\beta\)

\begin{equation*}

\abs{f(x)(g(x) - L_g)}=\abs{f(x)}\abs{g(x) - L_g} \lt N\abs{g(x) - L_g}.

\end{equation*}

Let \(\eps\gt0\) be given. Since \(\limit{x}{\infty}{g(x)}=L_g\) there is a real number \(B_g\) such that for all \(x\gt B_g\)

\begin{equation*}

\abs{g(x)-L_g}\lt \frac{\eps}{N}.

\end{equation*}

Take \(B = \max(\beta, B_g)\text{.}\) Then for all \(x\gt B\) we have

\begin{align*}

\abs{f(x)(g(x) - L_g)}\amp =\abs{f(x)}\abs{g(x) - L_g}\\

\amp \lt N\abs{g(x) - L_g}\\

\amp \lt N\frac{\eps}{N}\\

\amp = \eps.

\end{align*}

Therefore \(\tlimit{x}{\infty}{\left(f(x)\cdot

g(x)-f(x)\cdot L_g\right)}=0.\)

Proving Lemma 17.4.25 To prove Lemma 17.4.25 we need to guarantee that if \(x\) is large enough then

\begin{equation*}

\abs{f(x)\cdot L_g-L_fL_g}= \abs{L_g}\abs{f(x)-L_f}\lt \eps,

\end{equation*}

where \(\eps\) is an arbitrary real number. This is very similar to our goal in proving Lemma 17.4.24. But this time the “obvious” strategy will work. Almost.

That is, as long as \(L_g\neq0\) we can guarantee that \(\abs{L_g}\abs{f(x)-L_f}\lt \eps\) by taking \(x\) large enough to guarantee that \(\abs{f(x)-L_f}\lt \frac{\eps}{\abs{L_g}}\text{.}\)

We will need to handle the case \(L_g=0\) separately.

Proof of Lemma 17.4.25.

Let \(\eps\gt0\) be given.

There are two cases.

- Case 1:

-

\(L_g\neq0\)Because \(\tlimit{x}{\infty}{f(x)}=L_f\) there is a real number \(B\) such that if \(x\gt B\) then \(\abs{f(x)-L_f} \lt \frac{\eps}{\abs{L_g}}\)So if \(x\gt B\) then \(\abs{L_g}\abs{f(x)-L_f} \lt \abs{L_g}\cdot\frac{\eps}{\abs{L_g}} = \eps\text{.}\)

- Case 2:

-

\(L_g=0\)In this case \(\abs{L_g}\abs{f(x)-L_f}=0\cdot\abs{f(x)-L_f}=0\lt\eps\text{.}\)

Since the limit is zero in both cases we see that \(\tlimit{x}{\infty}{\left(L_gf(x)-L_gL_f\right)}=0\text{.}\)

Having completed the proofs of Lemma 17.4.24 and Lemma 17.4.25 our proof of Theorem 17.4.23 is now also complete.

The proofs of these two lemmas was not for the faint of heart. None of the individual pieces was difficult to follow, but putting them all together in the right order was delicate.

On the other hand, once Lemma 17.4.24 and Lemma 17.4.25 are known the proof of Theorem 17.4.23 becomes even simpler as Problem 17.4.28 shows.

Problem 17.4.28.

As you’ve seen using the limit definition (using \(\eps\) and \(\delta\)) to prove theorems is hard. But, as we said in Why We Prove Theorems, the whole point of proving theorems is to give ourselves more refined tools that we can use instead of resorting to definitions.

(a)

Now that we have Lemma 17.4.24 and Lemma 17.4.25 there is actually a simpler way to prove Theorem 17.4.23. Observe that

\begin{align}

\underbrace{f(x)\cdot g(x) - L_g\cdot L_f}_{\Gamma(x)} = \amp{}\underbrace{\left[f(x)\cdot g(x)-f(x)\cdot

L_g\right]}_{\alpha(x)}\notag\\

\amp{}+\underbrace{\left[f(x)\cdot L_g - L_f\cdot

L_g\right]}_{\beta(x)}\tag{17.9}

\end{align}

and complete the proof by citing Lemma 17.4.24 and Lemma 17.4.25 and the appropriate, previously proven, limit theorem.

Hint.

The right side of equation (17.9) is a sum.

(b)

Lemma 17.4.25 can also be proved without resorting to the limit definition (using \(\eps\) and \(\delta\)). Prove it by citing Lemma 17.4.24 and the appropriate, previously proved, limit theorems.

If you find yourself becoming completely absorbed in, and possibly even enjoying the details of these arguments you are surely a mathematician by inclination, if not by training (yet). There are more, and more interesting, results where these came from. Change your major and come join us. Sometimes we bring cookies.

Problem 17.4.29.

Theorem 17.4.30. The Limit of a Product at Negative Infinity.

If

\begin{align*}

\limit{x}{-\infty}{f(x)}=L_f \amp{}\amp{}\text{ and } \amp{}\amp{}

\limit{x}{-\infty}{g(x)}=L_g

\end{align*}

then

\begin{equation*}

\limit{x}{-\infty}{\left(f(x)\cdot g(x)\right)}=L_f\cdot L_g.

\end{equation*}

Problem 17.4.31.

Theorem 17.4.32. Limit of a Product at a Point.

Suppose that \(\limit{x}{a}{f(x)}=L_f\) and \(\limit{x}{a}{g(x)}=L_g\) for some real number \(a\text{.}\) Then

\begin{equation*}

\limit{x}{a}{\left(f(x)\cdot g(x)\right)}=L_f\cdot L_g.

\end{equation*}

Finally, we come to the limit of a quotient. Given how much trouble the limit of a product gave us, it is a little scary to think about proving that the limit of a quotient is the quotient of limits from the definition.

This trepidation is justified. It is very tricky to prove --- from the definition --- that the limit of a quotient is what we expect it to be. Fortunately we won’t have to. We now have enough theorems (tools) available that we no longer have to work directly from the limit definition.

However we will need to dispose of the following small detail.

Subsection 17.4.5 The Function \(f(x)=\frac1x\) is Continuous Wherever It Is Defined

Lemma 17.4.33.

You will need Lemma 17.4.33 to solve Problem 17.4.36 below. We will provide the scrapwork and leave the formal proof as a problem for you.

Scrapwork 17.11.

To keep things simple (this is scrapwork, after all) we will first assume that \(a\gt0\text{.}\) If we have an \(\eps\gt0\) then by Definition 14.1.15 we need to find a \(\delta\gt0\) such that if \(\abs{x-a}\lt\delta\) then \(\abs{\frac1x-\frac1a}\lt\eps\text{.}\) As usual we work backwards.

Combining the fractions we see that

\begin{equation*}

\abs{\frac1x-\frac1a}=\frac{\abs{a-x}}{a\abs{x}}=\frac{\abs{x-a}}{a\abs{x}},

\end{equation*}

so we need to find a \(\delta\gt0\) such that \(\abs{x-a}\lt\delta\) ensures that \(\frac{\abs{x-a}}{a\abs{x}}\lt\eps\text{.}\)

At first it appears that all we need to do choose \(\delta

\lt \eps\cdot a \cdot\abs{x}\text{.}\) If we could do that we’d have \(\abs{x-a}\lt\delta = \eps\cdot a

\cdot\abs{x}\) in which case

\begin{equation*}

\abs{\frac1x-\frac1a}=\frac{\abs{x-a}}{a\abs{x}}=\frac{\abs{x-a}}{a}\cdot\frac{1}{\abs{x}}\lt\eps.

\end{equation*}

But of course we’ve seen this before. Just as in the proof of Lemma 17.4.24, \(\delta\) cannot depend on \(x\text{.}\) So we need to replace \(\frac1x\) with a constant somehow. The Algebra here gets a bit delicate. We strongly recommend that you visualize each step of the following argument with a sketch like the one we used in the scrapwork for Theorem 17.4.18

Suppose that

\begin{equation*}

\abs{x-a} \lt\frac{a}{2}.

\end{equation*}

Then we see that

\begin{equation*}

-\frac{a}{2}\lt x-a \lt\frac{a}{2}

\end{equation*}

or

\begin{equation}

\frac{a}{2}=a -\frac{a}{2}\lt x \lt a+\frac{a}{2}=\frac{3a}{2}.\tag{17.10}

\end{equation}

Thus if we make \(\abs{x-a}\lt\frac{a}{2}\text{,}\) we see that \(0\lt\frac{a}{2}\lt x\) and so, from the right side of equation (17.10).

\begin{equation*}

\frac{1}{\abs{x}}=\frac{1}{x}\lt\frac{2}{a}\text{.}

\end{equation*}

Aside: Comment.

Therefore \(\abs{\frac1x-\frac1a}=\frac{\abs{x-a}}{a}\cdot\frac{1}{\abs{x}}\lt\frac{2}{a^2}\abs{x-a}\text{.}\) Thus if we choose \(\delta\) to be the lesser of \(\frac{a}{2}\) and \(\frac{\eps a^2}{2}\) we have everything we need to conclude that \(\tlimit{x}{a}{\frac1x}=\frac1a\) for \(a\gt 0.\)

END OF SCRAPWORK

Problem 17.4.34.

(a)

(b)

If \(a\lt0\) we could replicate the proof in part (a), but keeping track of all of the sign changes will be burdensome. Otherwise it is really the same proof. Instead, notice that if \(a\lt0\) then \(-a\gt0\) and so by part (a)

\begin{equation*}

\limit{y}{-a}{\frac1y}=\frac{1}{-a}.

\end{equation*}

Use this observation to prove that if \(a\lt0\) then \(\tlimit{x}{a}{\frac1x}=\frac1a\text{.}\)

Armed with this and our Limit Theorems, we can tackle the proof of the next theorem without resorting back to definitions.

Theorem 17.4.35. The Limit of a Quotient is the Quotient of the Limits.

Suppose \(a\) is positive infinity, negative infinity, or some real number, that \(\limit{x}{a}{f(x)}=L_f\text{,}\) and that \(\limit{x}{a}{g(x)}=L_g\neq0\text{.}\) Then

\begin{equation*}

\limit{x}{a}{\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}}=\frac{L_f}{L_g}.

\end{equation*}

Problem 17.4.36.

(a)

Prove that if \(\limit{x}{\infty}{f(x)}=L_f\) and \(\limit{x}{\infty}{g(x)}=L_g\neq0\) then

\begin{equation*}

\limit{x}{\infty}{\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}}=\frac{L_f}{L_g}.

\end{equation*}

(b)

Prove that if \(\limit{x}{-\infty}{f(x)}=L_f\) and \(\limit{x}{-\infty}{g(x)}=L_g\neq0\) then

\begin{equation*}

\limit{x}{-\infty}{\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}}=\frac{L_f}{L_g}.

\end{equation*}

(c)

Prove that if \(a\) is some real number, and \(\limit{x}{a}{f(x)}=L_f\text{,}\) and \(\limit{x}{a}{g(x)}=L_g\neq0\text{.}\) Then

\begin{equation*}

\limit{x}{a}{\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}}=\frac{L_f}{L_g}.

\end{equation*}

We have one last loose end to tie up. Recall that Theorem 16.1.13 in Chapter 16 says that a limit exists if and only if the right– and left–hand limits both exist and are equal. One-sided limits are informally defined in Definition 16.1.12. But an informal definition is not sufficiently precise to support constructing a proof, so here is the formal Definition of a right–hand limit.

Definition 17.4.37. Right-Hand Limit.

Suppose \(f(x)\) is defined on some interval \((a,b)\text{.}\) Let \(L\) be a real number. We say that

\begin{equation*}

\rtlimit{x}{a}{f(x)}=L

\end{equation*}

provided that for each \(\eps\gt0\text{,}\) there is a \(\delta\) with \(0\lt\delta\lt b-a\) such that if \(a\lt x \lt

a+\delta\text{,}\) then \(\abs{f(x)-L}\lt\eps\text{.}\)

Problem 17.4.38.

(a)

Using Definition 17.4.37 as a model, state a similar definition for

\begin{equation*}

\ltlimit{x}{a}{f(x)}=L\text{.}

\end{equation*}

(b)

As you can see, rigorous demonstrations, as necessary as they are, can become complicated and tedious. Perhaps this explains why the practice of Calculus predated its theory.

We have defined the derivative by Definition 13.2.3, derived all of our differentiation rules via this definition, and shown — rigorously — that founding Calculus on the theory of limits gives us all of the properties we found useful in Part I of this textbook. At long last, this places a solid, logical, and rigorous foundation underneath the Differential Calculus of Newton and Leibniz.

And Bishop Berkeley has nothing left to criticize.